Path(s) to Success

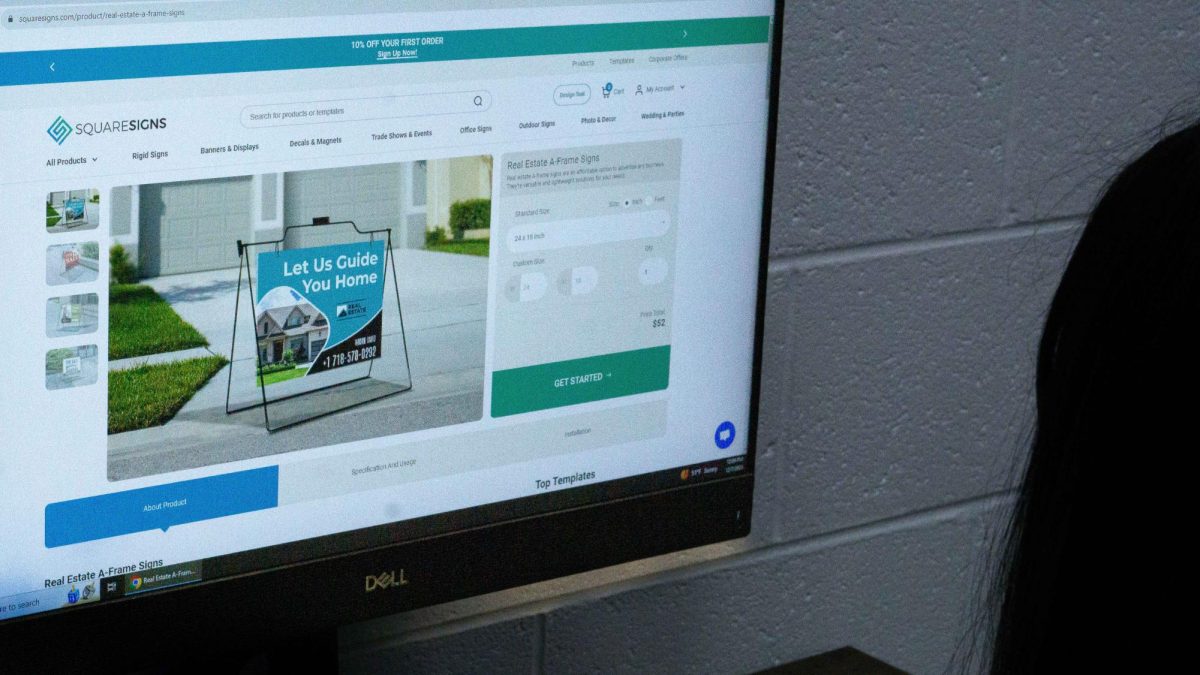

Students work diligently in a marketing class, exploring a possible option for their futures.

Senior year, a supposedly stress-free recovery period from previous academic trauma, is not turning out to be as carefree as expected. Every student was told that junior year was going to be the hardest period they encountered in high school, with one student testifying, “For juniors especially there’s so much competitiveness, they’re all freaked out about 80s or 85s.” But while the unhealthy struggles of being a junior are widely known, the agonizing frenzy of impending futures as youth comes to a close is unrecognized. It’s as if students are being kicked down a pavement that leads to a four year degree, when many would be better suited to a detour.

With a diploma looming on the horizon, students feel pressure to map out each step to success; however, its definition is up in the air. Many glance to peers or parents for guidance and end up taking an unfit route. Then they have to turn around and become a cartographer all over again. The counseling department has been working to conserve students’ time and energy as they emerge into society by introducing alternative options to college in their senior seminars. “So, I think, we definitely don’t push the ‘College is for All’ narrative,” said a counselor, “Right now, kids are so pushed to go to college, but we’re seeing a lot of kids after their first year not returning and going into trade work.” It’s become clear that for many graduates, college leads to a u-turn, but it’s been tough to dismantle the idea that university is a necessity.

For the longest time, a 4-year degree was considered a guarantee for a steady and fruitful life. This idea was drilled into parents, as, “That was kind of something that was really pushed in the 90s and early 2000s,” remembers a counselor. Truly, they’re trying to help, but in an evolving world, they might be holding their children back. The average amount of university loan debt in the U.S. is currently $30,000. In comparison, apprentices can make money while they learn.

However, it’s nearly impossible to teach an old dog new tricks, even armed with statistics. A student confirms that they have limited choices due to household beliefs, “Honestly, for me, when it comes down to it, I would go to college because my parents expect me to go.” This is especially true in immigrant families because, “The reason they wanted to come to America is because they wanted a better education, a better life for me and my brother and our family generations after.” To them, college is the direction to happiness and they are unable to proceed any other way.

The responsibility of fulfilling ancestors’ expectations is difficult to cope with. “I see people having panic attacks because they have Bs in AP classes, and I feel so upset for them because they shouldn’t have that social burden. They’re like 16,” says the same student from before. They believe it’s necessary for the counselors to address this issue, for them to defuse academic competition before the student body crashes and burns. A counselor recognizes the struggle, observing that, “If they fail, their parents will never let them hear the end of it, and I think that’s part of the problem.” There have been attempts to guide young people away from perfection and towards wellness and balance, but generational pressure persists. “If you’re into art, take art, if you’re into music, do a music class. You shouldn’t be doing 7 APs. That’s unhealthy,” advises the counselor. They believe it’s okay to fail in high school. They believe it is where failure should occur, because it’s easier to recover as a teenager in public school, rather than in an education that an entire livelihood depends upon. High school doesn’t exist simply to decide which college options are available, because the future isn’t a one-way road. Failure can steer students a way more suitable to their strengths.

There is the occasional student who doesn’t wrestle with the duty of attending university. Regarding the presentation to seniors and the bit about trade school, one admits, “I was a lot more interested than the rest of the seminar because the rest of the seminar was stressful and all about college.” This person leans towards physical work, and recognizes that they don’t fit the mold for a four-year degree. Plus, they are excited by the prospect of money: “Trade school pays better, it’s not as expensive.” Enormous loans won’t be haunting their future, and neither will the vision of what their life could be if they embraced their talents. They have a clear and straight path to personal success.

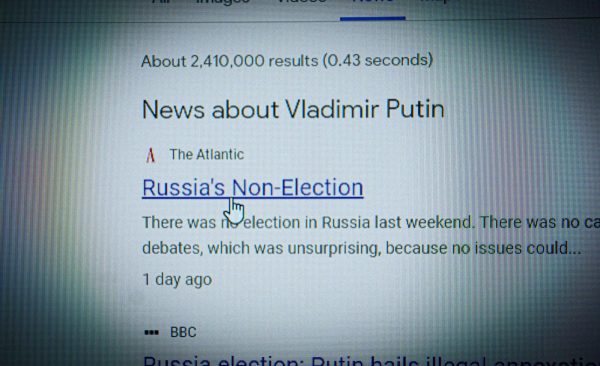

This road is often obscured by others’ vision. Whether it be parents, peers, or posts on social media, skilled professions are seen in a negative light. The thoughts of university supremacy are commonly recognized, but a student explores what other reasons might be the cause, “I feel like when you see media stereotypes a lot of the time, especially how these kinds of jobs are represented in our media, they don’t have good highlights on them.” The counselor agrees, “I like to remind kids, some of them think of plumbing, and they’re like, ‘Ew!’ and I’m like, ‘Who built the Georgia Aquarium? Who builds waterparks?’ Those are all plumbers.” They encourage students to think outside the box and to think beyond the traditional ideas presented to them. Today there is not just one course of action following high school, and students need to be introspective about the steps they take.

How do you think the site looks? As you read this, I'm probably tinkering around with it, so say nice things. While awards and merit are important, my...